Chopin's Mazurkas - Part 3 @ r11

And we're back with another exciting installment of me listening to Chopin's Mazurkas and then talking to myself about them (previously: part 1 and part 2). We begin on Op. 24, No. 1.

Quatre Mazurkas

For a monsieur Comte de Perthuis

Op. 24, No. 1 in G minor

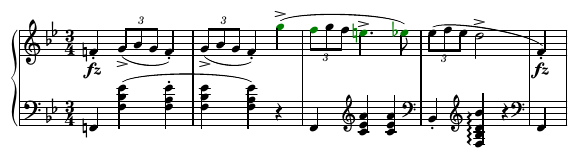

I'm excited to announce that Chopin has returned to form by starting with a V - i

progression. A return to the classics (see part 1 for more details).

The main theme features some more "gypsy" style scales, with what I think is called

the altered Phyrgian

Hungarian minor scale,

i.e. harmonic minor with a raised 4th. In this case some rogue

C♯'s.

The next section features some interesting echoing by the left hand. The 9th jump followed by a descending chromatic which was repeated a phrase earlier in the right hand.

The rogue C♯ makes another appearance to help transition from E♭ back

to G minor by use of what appears to be a progression of

E♭7 →

A7♭5 →

D7 and finally ending back at

Gm. That "V of the V"

progression which utilizes the ♭5 is a harmony that is not uncommonly seen

seen in Chopin's music, and the Romantic era in general (e.g. Chopin's 2nd

Ballade)1.

Ragtime music also makes very heavy use of the "V of the V"

progression, although you don't see a ♭5 very frequently.

V of the V" progression in Chopin's

Ballade No.

1

V of the V" as seen in Scott Joplin's famous

The

Entertainer

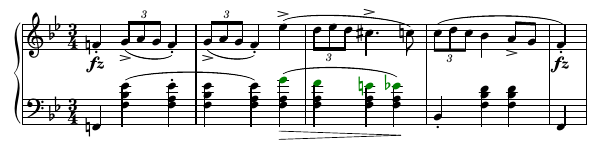

Op. 24, No. 2 in C major

A nice happy number, to contrast the gypsy-style funeral dirge of No. 1. The brief F major arpeggio in the B section reminded me of Chopin's F major Etude Op. 10, No. 8. It even has a similar trill. Although it's like three times faster and covers three times as many octaves.

This is followed by perhaps the clunkiest modulation I've heard from Chopin. You don't

frequently see a modulation beginning with a tritone. Also notice that the

V → I progression is back on the menu as well!

The tritones continue as the left hand takes over the melody, this time in D♭ as opposed to A♭.

And again my score is missing a note that's present in the recording I'm listening to. A rogue A is can be heard but not seen right before the repeated quarter note chords at the end. Time to investigate once again.

- Arthur Rubinstein does not play the phantom A's2

- Martha Argerich does play the phantom A's3

- Rafał Blechacz does play the phantom A's4

- Krystian Zimerman does play the phantom A's5

In conclusion, play the A's. If Zimerman and Argerich are doing it, so should you.6

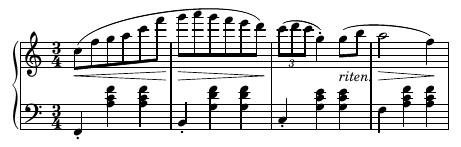

Op. 24, No. 3 in A♭ major

Another one starting off with the V → I

progression. I don't know why that fascinates me so much.

The A section is pretty simple, there's not a lot to say about it. It follows

a simple chord progression (just I, IV and V)

and nothing crazy happens. Barely even any passing tones or anything harmonically

complex. It's just simple and easy to listen to.

The B section brings out some more complex harmonies. I particularly liked the left hand, which plays continuously resolving °7 chords. And I didn't notice this as I was listening and following the score the first time, but that penultimate chord in the left hand is actually a G7♭5 (see, I knew the 7♭5 chords were ubiquitous). At first glance I assumed that D♭ was a D♮. Isn't it wonderful how the universe just aligns like that?

The end of the B section reminds me of the beginning of Chopin's Ballade No. 2, but that's probably because I was just refamiliarized myself with it after trying (in vain) to find the 7♭5 chord progression from the previous mazurka.

The little coda brings this happy little mazurka to a close. Although it ends on the third, which is almost ominous. Of note: the marking starting in the fifth bar from the end (perdendosi) is something I've literally never seen before. I had to look it up, and it means (essentially) "get slower and quieter".7

But, you know, much more romantically.

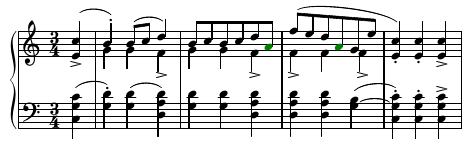

Op. 24, No. 4 in B♭ minor

Yes, it's true. Another mazurka starting with the V → i

progression. Although technically, this one has a pretty weird intro with some strange

chromatic dissonance, before getting to F7 and finally B♭m.

I like this one. The A section is full of Chopin-esque-ness, with complex harmonies, some counterpoint, using a lot of the piano's range, and wide dynamic shifts. This is what Romantic music is all about. After the B section, the A section is revisited but this time with even more counterpoint. Reminds me of Chopin's 4th Ballade, where every time the main theme is repeated there is more counterpoint and more complex harmonies.

The piece eventually has a little Coda (marked calando) in B♭ major, and one part caught my eye:e it's a very strange spelling of one instance of a repeated chord, and honestly it just looks like a mistake.

After some investigation, the E/C♯ spelling is directly from the manuscript8 (which I suspected, since it's so weird that no editor would spell something like that). However, Chopin (or whoever he hired to transcribe for him) did appear to scribble out the first try, so maybe there was some confusion somewhere. Or maybe he was just drunk.

Of all the mazurkas so far, this one is definitely my favorite.

Downloads

- Lilypond source used to generate the graphics used in this article.

- Actually, this is incorrect, as I misremembered the chord voicings in Chopin's 2nd Ballade (there is a B7♭5 chord voicing at the very end, which eventually leads to E7 and then to Am, but there's like 8 measures of stuff in between the chords, so I don't think it counts). And then I couldn't actually find an example of it in less than 5 minutes so I gave up. It's possible that chord progression is not nearly as common as I thought in Romantic music.

- Rubenstein's performance of Op. 24, No. 2 on YouTube

- Argerich's performance of Op. 24, No. 2 on YouTube

- Blechacz's performance of Op. 24, No. 2 on YouTube

- Zimerman's performance of Op. 24, No. 2 on YouTube

- If possible, of course.

- From this source, perdendosi was also used by Chopin in his C minor Polonaise (Op. 40, No. 2), and by Beethoven in his 31st Sonata (A♭ major), which nobody remembers because it's sandwiched between the Hammerklavier and the famous and influential No. 32.

- Image taken from Polona